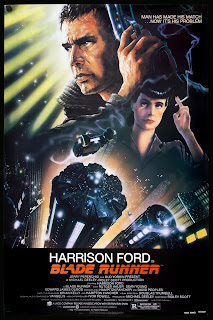

Even though Blade Runner takes place in the future (well, what was then the future of 2019), it strangely feels more evocative to me of 1982 than any other film from that summer. Other summer of '82 films were set in the actual present day, of course, like Poltergeist and Fast Times at Ridgemont High, and those do have their own nostalgic triggers of dated fashions and era-specific slang but as soon as Blade Runner opens on 2019 Los Angeles, with flames erupting from industrial chimneys into the night sky, I'm not in the future, I'm in the past. It doesn't look like 1982, it doesn't sound like 1982 (Blade Runner composer Vangelis may have had a #1 Billboard hit the previous year with his instrumental title piece for Chariots of Fire but the Top 40 in '82 belonged to the likes of The Human League and Toto), but somehow it is 1982, in all its nerdy glory.

Over the years, I've never been able to get comfortable with any of the various revised editions of Blade Runner that director Ridley Scott has supervised. While I'm glad he's had the chance to realize the movie to his satisfaction, that initial compromised adaptation of Philip K. Dick's 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sleep? is the one I fell in love with. No matter how true to his artistic intent the Director's Cuts are, they just aren't Blade Runner to me. The theatrical cut made such a stamp on me that my mind rejects any move to tamper with it. But when it comes to a movie about the differences between humans and replicants, though, I think it's only appropriate that I shouldn't be able to divorce irrational sentiment from my appreciation for it. I remain emotionally attached to Blade Runner in its original form.

If I don't hear Harrison Ford's voice over narration, as we first meet his world weary Rick Deckard, saying "They don't advertise for killers in the newspaper. That was my profession. Ex-cop. ex-Blade Runner, ex-killer," I'm checked out.

Blade Runner is more than a movie, it's a memory and as Blade Runner demonstrates, there is a sanctity to memories. Even artificial ones are worth fighting for. Blade Runner's replicants pine for and cling to pasts that were never really theirs while desiring open-ended futures to call their own. Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), Pris (Daryl Hannah), Zhora (Joanna Cassidy), Leon (Brion James), and Rachael (Sean Young) long for more than they've been given and that puts them in contrast to the humans of Blade Runner like Deckard or his supervisor, Bryant (M. Emmet Walsh), who have a flat, cynical take on their own existence and don't show any special interest in imparting their lives with meaning (as Deckard says in his voice over: "Sushi, that's what my ex-wife used to call me: cold fish."). The human characters in Blade Runner all take for granted the fact that their lives intrinsically matter by simple dint of biology. No matter how much they might squander their existence there's an authenticity to their being that can't be questioned. Replicants, however, are left longing for validation.

The lives of replicants are someone's else's daydream, an accumulation of stolen, appropriated details, with fabricated props like photographs to help complete the illusion. The German word fernweh is translated as "an ache for distant places," and the beauty of Blade Runner is that it identifies that distant place as oneself. It is a destination that no replicant can ever quite reach and no human seems to give much thought to.

Replicants inhabit their manufactured bodies but struggle to instill them with meaning. Tyrell Industries' CEO Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel) says to Roy Batty that "the light that burns twice as bright burns half as long" but that is no comfort to a being that simply wants more life because life, even an artificial life, is preferable to nothingness. Humans can comfort themselves with dreams of an afterlife but there is no afterlife for machines. There is only existence or non-existence. Replicants will not meet their loved ones in some celestial palace. Their memories of their parents and siblings aren't real, there is no one waiting to greet them on the The Other Side and Blade Runner evokes that particular, peculiar sadness.

That sort of melancholy wasn't what audiences were craving in the summer of '82, though. The previous summer Harrison Ford had dominated the box office with Raiders of the Lost Ark and when it was released on June 25th, 1982, audiences quickly realized that Blade Runner was not in any way a reprise of Raider's crowd pleasing, cliffhanging thrills. It wasn't even the kind of intense but exhilarating roller coaster ride that Scott's Alien (1979) had been. Instead this big budget sci-fi film was morose and steeped in sadness. The action of Blade Runner was minimal and what little action there was usually ended with Deckard killing a woman. Replicant women, perhaps, but deeply unpleasant just the same. Seeing Ford as Indiana Jones giving Nazi scum what's coming to them in Raiders was one thing but to see him as Deckard shooting a fleeing Zhora in the back was something else.

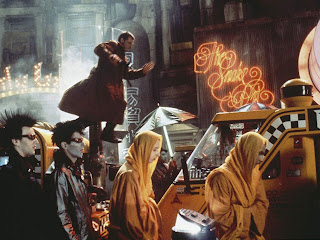

When Deckard has the opportunity to take Zhora out, he takes it and as dangerous as she may be, to see Deckard gun her down in such a ruthless (some would say cowardly) way, sending her crashing through sheets of glass to bleed out in the street, is not what audiences either expected or wanted to see from a movie hero. There is no way to spin Deckard's actions as that of a good man and Scott never attempts to (the most bitter sounding words in the entire movie belong to Edward James Olmos when Gaff says to Deckard "You've done a man's job, sir."). When Deckard shoots Pris in J. F. Sebastian's apartment, her violent death throes as her lithe body spasms out on the floor are horrific to watch. That we are never meant to root for Deckard in his mission, that it always is portrayed as nothing but cruel is the main reason why Blade Runner didn't catch on in '82. Americans at the time wanted to feel good about themselves and be sure of their purpose. They didn't want to see protagonists consumed by doubt. To have a movie where the supposed hero could not convince himself that he was in the right was anathema to most Americans in '82.

Man vs. Machine has been a perennial theme of science fiction, from the malevolent HAL 9000 in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) to the deadly, malfunctioning androids of Westworld (1973) to the relentless T-800 in The Terminator (1984) but Blade Runner is the rare instance of the empathy being on the side of the machines. Replicants aren't just physically superior to humans, they possess a sense of morality and a soul that the humans around them lack.

What even critics at the time had to concede was a triumph for Blade Runner was its groundbreaking look. To regard Blade Runner as purely an achievement of its extraordinary production design, though, is to not understand how well Scott uses all the tools at his disposal. When the design of a film says so much, you can't just glibly wave it off as superficial. The sets are not just simply environments that the characters are standing in and delivering their lines, like the living room of a sitcom. These environments complete these characters. The style is the statement. You can't separate how Blade Runner looks from what it's saying and what it's characters are feeling.

In the forty years since its release, no other cinematic vision of the future has surpassed Blade Runner. From 1982 on, when filmmakers have set out to imagine the future, Blade Runner has been the default starting point. When the look of a movie is so groundbreaking, so transformative that it influences everything afterwards, there's no denying that you're dealing with a classic. The greatest testimony to Blade Runner may be that it's been the vision of the future for so long, I forget what the future looked like before it.

After it tanked in theaters, critics likely assumed that we'd soon stop talking about Blade Runner. But it has gone on to defy all expectations by having a life that has stretched well beyond what any would have guessed. Deckard's final words in the theatrical cut to describe Rachael as the pair head off to an unknown future together apply to the surprising longevity of Blade Runner itself.

It's a movie with no termination date.

No comments:

Post a Comment