Thing is, though, I have really liked director Scott Derrickson's previous films. Sinister (2012) is the one that gets the most attention and that's a great one, just a tremendously effective shocker, but I think The Exorcism of Emily Rose (2005) is terrific too. He even made the best of the direct-to-video Hellraiser sequels with Hellraiser: Inferno (2000) so when he puts out a new horror movie, it's kind of a big deal. Bottom line, I decided to suck it up and see The Black Phone and, damn, I'm glad I did because it's fucking fantastic. It doesn't match the sheer terror of Sinister but it's still damn scary and, more importantly, it is a much more emotional movie, hits on a deeper level and although the subject matter is grim, Derrickson and scripter C.Robert Cargill (collaborating again with Derrickson after Sinister and Doctor Strange) find a way to make this adaptation of the Joe Hill short story suspenseful but not exploitative. It never wallows in the pain of The Grabber's victims or lingers on his deeds. There's enough there to know the stakes involved but Derrickson knows when to pull back and when to let suggestion do the work.

As much as I was dreading the way the kids in peril aspect of The Black Phone would be handled, it turns out that's only part of the misery its young characters have to face. Brother and sister Finney (Mason Thames) and Gwen (Madeleine McGraw) live in constant fear of enraging their alcoholic father Terrence (Jeremy Davies, very good in a role that could've have easily been played as a one-dimensional shitbag). On top of that, Finney faces bullies at school who are looking to kick his ass. He gets a brief respite when the school's toughest kid, Robin (Miguel Cazarez Mora), lets it be known that Finney is his friend and therefore off limits but when Robin becomes another victim of The Grabber, it's open season on Finney again. So these kids already have to navigate a brutal existence on a daily basis, even without the looming specter of The Grabber.

Even if you were lucky enough not to live in an abusive home, the '70s were still a savage time to be a kid. Seeing the bloody fights that occur in this movie, with kids just fucking beating on each other, it brought back memories for me of being a young kid back then and seeing the same kind of violence and having it just be a normal part of life.

Every time is a hard time to be a kid but the '70s felt very raw in its own particular way. Adults were largely indifferent to what kids were up to, being wrapped up in their own personal shit during the "Me Decade." It was a time when more and more kids were becoming children of divorce or else they grew up with both parents together but with both of them working so either way most kids of the '70s were latchkey kids and so much of their lives were ungoverned and unsupervised, no matter how much scary shit was going on.

Kids had to take the bus home to empty houses or walk to and from school alone all while the news was frequently filled of stories about predators, with the police unable to crack these cases and communities living in terror. This was long before cellphones and iphones and surveillance cameras and so on. There was a sense then that people could easily just vanish that isn't quite the same in today's world. Not that horrible things don't still happen, of course, but the world used to be much more advantageous to predators than it is today.

The Black Phone nails the vibe of what it was like to grow up then. Even with The Grabber on the loose taking kids left and right, the kids in The Black Phone are still roaming the streets alone rather than being safe at home closely guarded by their parents and that is a very '70s thing. If you survived your '70s childhood, luck played a part.

The fear of a predator stalking the neighborhood and snatching a kid here and there might seem quaint or even, in its own way, innocent to today's generation of young people who have to live with the possibility of having a random mass murder occur during the middle of their school day but there was a particular type of creeping terror that hung in the air in the '70s and Derrickson and Cargill do an expert job of tapping into it.

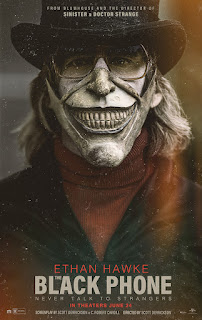

Ethan Hawke is fittingly spooky as The Grabber, sporting a series of eerie devil masks designed by Tom Savini. I don't know if I would say it's a particularly great performance but it's effective enough. It gets the job done. Honestly, I actually like that this is a movie where the villain doesn't steal the show, The focus is very much on Finney and Gwen (both Thames and McGraw are outstanding in their roles) and there's no attempt to make The Grabber cool or appealing. We don't even get a backstory for him. That might strike some as a weakness but I think it was the right choice here. What do we really need to know about The Grabber? There's no need to give any kind of psychological justification for his crimes. All we need to know about is the terror he inflicts.

With Gwen having psychic abilities that she inherited from her deceased mother and the phone calls from the dead that Finney receives courtesy of the titular device in the Grabber's basement, there is a supernatural component that puts The Black Phone just enough in the realm of the fantastic to make it more than a drab story about a child murderer. The balance of gritty realism and supernatural horror is a combo that other horror movies have had but it works especially well here. The supernatural elements allow this Good vs Evil tale to attain an almost fable like quality. At the same time it remains a movie filled with bitter truths and harsh realities. The wins the characters achieve feel earned but it's also understood that darkness will continue to play a part in their lives.

Derrickson choose to leave the sequel to Doctor Strange to direct this instead as it felt closer to his heart and seeing it, it's clear that he made the right choice. I really think that Derrickson has made a special film with The Black Phone. It's a model of how to do mainstream horror right and it shows what can be done in the genre when everyone involved isn't just phoning it in.