In the wake of The Flash's disappointing box office, things are looking grim on the DC front. Or at the very least, uncertain. It seems clear that audiences are not buying what DC is selling at the moment and it's unclear what's going to turn that around. What you can bank on is that WB will never throw in the towel on the DC universe. That is an IP gold mine that no studio is ever going to forsake. So no matter what kind of failures the DC universe suffers, the movies will keep on coming. It's just a matter of what the latest plan for the DCU will be.

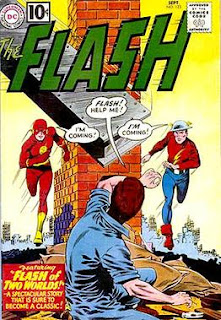

For long time comic fans, the great irony of DC's current movie dilemma is how badly they've botched the multiverse aspect of their universe and, more than that, how they've forfeited that space to Marvel. For years, the multiverse was DC's thing. While Marvel had one streamlined universe with one continuity, DC was the comic universe that dealt in a myriad of multitudes. To explain the aging of their characters and to explain the multiple versions of their characters, DC had a multiverse that allowed Golden Age characters to exist in their own universe and Silver Age characters to exist in theirs, with the opportunities for crossovers between the two. One of the most legendary comics in DC history is 1961's Flash #123, an issue in which readers were presented with the tale of the "Flash of Two Worlds," with present day speedster Barry Allen meeting the Golden Age Flash Jay Garrick and it was the popularity of this issue with readers that led to a series of annual crossovers between the Golden Age Heroes of the Justice Society of America, whose roster included the likes of Hourman and Dr. Fate and the present day Justice League.

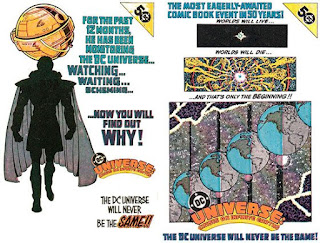

For decades, DC had used the multiverse to account for continuity errors or to simply allow alternate versions of characters to remain in play, just not within the primary universe. But by the '80s, the thinking within DC was that to compete with industry leader Marvel, they had to emulate Marvel's singular continuity and trim the fat from their universe, paring it down to just one world. So 1985's Crisis on Infinite Earths was the big move on DC's part to rid themselves of the multiversal baggage that had built up over the course of fifty years and, hopefully, make their universe more new reader friendly. It ended up being an imperfect act of housekeeping, with editorial at the time failing to make a totally clean break between the past and present of DC. Remnants of prior history survived here and there and some characters were given a fresher slate than others. But even though it was a slightly sloppy segue way from one era to the next, overall it worked and the bottom line was that readers understood that there was now one connected DC universe going forward.

That lasted until 2011 when DC decided to reinstate the multiverse with the Flashpoint storyline. So on the publishing side, decades after changing their universe to be more like Marvel, DC decided to get back in the multiverse game. Meanwhile, in the movie and TV realm, while Phases 1 through 3 of the MCU had been very liner, moving from Point A to Point B to lay down the foundation of the MCU, going into Phase 4, the new watchword of the MCU, according to Kevin Feige, would be "multiverse." On the Sony side of Marvel, this was also true with 2019's animated Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse being all about the vast multiverse of Spider Heroes, including everyone from Spider-Noir to Spider-Ham. While WB/DC was still in the process of struggling to create a singular shared universe to match the MCU, Marvel was already moving on to stake their claim as the masters of the multiverse, dubbing Phase 4 "The Multiverse Saga." What historically used to be DC's domain has now become perceived by the public at large as a Marvel thing. The multiverse was something that DC chose to give up and now they're forced to play catch up.

With Phases 1 through 3, Marvel provided a model on establishing a cinematic universe but following their example proved difficult for WB/DC. Now in Phases 4 and 5, Marvel has been showing how to establish a cinematic multiverse but, again, as it was when it came to building a linear universe, when it comes to their multiverse game, WB/DC still just wants to short cut their way to where Marvel's at without putting the same effort in.

Marvel has staked out the multiverse front with Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018), Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021), Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022), Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (2023) and the Disney+ Marvel shows Loki (soon to debut its second season) and the animated What If? (also due to have a second season). They've dominated this space in a way that WB/DC is ill equipped to compete with.

Case in point: The Flash.

Even with Marvel beating them to the punch, The Flash still could have made the statement that DC has its own bragging rights to the multiverse but it did not send that message. It's not the fault of the filmmakers so much as the fault of a fickle studio demanding last minute changes. First and foremost, the problem that hinders WB/DC is that they lack the strong guiding hand that Marvel has and the willingness to stay the course and see things through. Whether that will change with James Gunn, who knows? For now, DC looks like a company that's been forced to play a weak hand.

Across the Spider-Verse makes the idea of seeing spin offs with Spider-Punk or Spider-Gwen and others a very welcome possibility. Multiverse of Madness, Loki, and What If? showed that there's endless, and endlessly surprising, variants on the Marvel universe. For its part, The Flash leaves audiences wondering "What was up with Nicolas Cage as Superman?" I say when you're trying to thrill and excite an audience on the possibilities that lie within your multiverse and you choose to waste screen time (and FX dollars) on an in-joke within an in-joke that is pitched to an incremental number of viewers - and even then is really not so much a "joke" at all but simply a reference (you not only have to know that Nicolas Cage was up to play Superman in a '90s Tim Burton movie that never happened, you also have to know that producer Jon Peters infamously insisted that he should fight a giant spider) - you're doing it wrong.

It's even more galling that while it goes out of its way to reference a version of Superman that never even existed, The Flash completely passed on the opportunity to honor the CW's Arrowverse, which ironically actually was successful in creating a live action, interconnected DC multiverse in a way that the movies haven't been. WB/DC will of course keep trying and perhaps in the James Gunn era the potential of the DCU will finally flourish. For now, though, the DCU and its pantheon of heroes and villains are mired in a mismanaged multiverse.